The face goes blank, the eyes widen and an arm stretches out, index finger leading as if to greet ET. He’s slipped into automated curiosity, an autopilot for exploring the world around him, activated by the presence of anything new or out of the ordinary. At five years old that’s pretty much everything he sees. Under normal circumstances it’s a good thing. A biological imperative to learn, develop and understand the world around him. Today, for me, that’s a problem. Today I have a fresh scar on my neck concealed beneath a large white bandage that might as well be a giant red button and he’s heading straight for it.

Perhaps I should explain how I got here. About a month before that kids finger began to make a beeline for some very tender and fresh scar tissue I was sitting in the Doctor’s office in a small clinic at the heart of the Izu Peninsula. What had brought me here was my third cold of the year. I teach at a day care centre, catching a cold every couple months is pretty much a quarterly contractual obligation, so usually nothing to write home about. Except in this case it had had something of a knock on effect. It had caused a small epidermal cyst in my neck to double in size and so I made my journey to the heart of Izu, to this tiny rather ramshackle clinic, to begin my guided tour through the Japanese health service.

Alongside me in that room, aside from myself, my friend and the doctor were a pharmacist, another patient behind a curtain and three nurses whose sole job appeared to be smiling at me with their heads at a jaunty yet unthreatening thirty-five degree angle. In smaller towns, where the tone of your skin is liable to make you something of a B-list celebrity, it’s perhaps better to forget all thoughts of privacy.

Well-worn cliché number one, Japanese people stare at foreigners, now attended to we move onto number two; the notoriously low English level of the Japanese. How low? Well, my first Doctor’s professional thoughts as to my treatment were that,

“Considering the language difficulty, I recommend you go home.”

Hardly what you want to hear when you’re speaking to a doctor. Especially so when a return trip home is liable to set you back a thousand pounds and result in the loss of your job by your absence. Particularly when you are legally obliged to pay into the very health system that has just decided to inform you, in Japanese, that even though you have barely uttered a word of English to the doctor, that despite turning up with a Japanese friend willing to translate for you, that the doctor’s phobia of the English language is so great you ought to consider repatriation.

Having ignored this advice and moved onto a larger hospital, with a letter of recommendation from the first Doc (she was freaked out by English, not unprofessional), I’ve since made it out of the Japanese health system alive and well. Aside from the suggestion of flying over two thousands back home for a minor medical ailment, I’ve had a positive if somewhat complicated experience. So here’s some advice for those who’ve yet to venture down the red tape, rabbit hole.

Work on your Kanji

Let’s face it, Kanji (Chinese characters) is hard. Not impossible, but reaching the level of competency required to understand medical Japanese is going to be pretty far in your future. So if you live outside of any major metropolitan area in Japan and your Japanese isn’t fully up to scratch you’re going need a native speaking friend or co-worker to help guide you through all this, because while foreigners in Japan are legally obliged to pay into the national health insurance scheme there doesn’t seem to be much in the way of English, Portuguese or Chinese language help. No one is looking for an on call translator, but the odd bit of multi-lingual paperwork would be helpful.

That Japan has only recently introduced full time translators to its major airports would suggest that help for those who haven’t mastered their Japanese quite yet might be some time coming. An ethnic Japanese population of around 98% might suggest it might not even arrive at all.

Generational Issues

The one thing I really wasn’t expecting, aside from the suggestion I get my minor ailment treated back in England to save on language difficulties, was how much my ability to understand my doctor’s Japanese would change from person to person.

My first Doctor, age fifty something, 70% understanding.

My second Doctor, age thirty something, 80% understanding.

My third Doctor, twenty something… 0%.

Take a moment to consider how you, your parents and your grandparents speak. Same language but great, impossibly deep chasms can separate the young from the old in terms of syntax and phrasing.

In this case my third Doctor sounded like she majored in cuteness at Hello Kitty University. Her conversation may have been peppered with the cute linguistic, idiosyncrasies of the young in a country obsessed by all things, ‘Kawaii’ (Japanese for cute), but there is something quite disturbing in having someone who could voice a Muppet inform you of the length of the scar you’re about to receive.

Even more staring than usual

Whatever your problem is, pray it isn’t sexual or highly visible. Particularly if like many English speaking foreigners working in Japan you’re a teacher. Because your students are going to ask what’s wrong, your colleagues will ask what’s wrong and then your boss will.

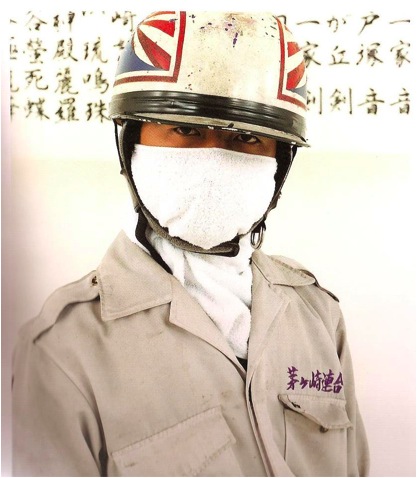

If it’s visible, as the bandage on my neck was, prepare to be stared at even more than usual.

This place is not designed for the likes of you…

No not foreigners, though we certainly aren’t at the top of the list of people to consider. I mean anyone under sixty-five. When I arrived in the waiting room of a hospital early one morning, ticket stub in hand to wait for my turn with the doctor, I realized that at precisely eight in the morning I was the only person below retirement age in an utterly jam-packed waiting room.

There’s a fairly simple reason for this phenomenon in my inaka (countryside) hospital; you can’t make appointments or advanced reservations. It’s first come first served and the old folks are up and waiting outside that doctor’s door at six a.m. on the dot. All this despite the fact that that doctor’s door will not open until exactly eight a.m.

And finally, for those who teach… have cat like reflexes

I teach at a day care centre once a week. It has its up and downsides. Upside, enthusiastic, endlessly entertaining kids. Downside, they don’t know what personal space is. Nor are their social skills too refined by age five.

As such when entering a classroom I got a, “ Hello Masshu (my name once Japanafied) Sen…. ehhh.” That final ‘ehhh’ was delivered with a pretty impressive synchronized head tilt and thirty little faces that screamed, why the hell is there a bandage on your neck!

But this isn’t sympathy, it’s curiosity and while this kind of curiosity is unlikely to lead you to such a fate as enjoyed by overly inquisitive felines it is liable to attempt to jab you wherever it hurts.

Maybe that’s not such a bad thing though, considering where they usually try to poke you.